Most people know yoga as a physical practice, but that’s only a tiny part of what it has to offer. More importantly, yoga offers us a way to cultivate a peaceful mind and to lessen the suffering that is part of human existence.

The Yoga Sutras present a systematic process to work towards that noble goal. Although they date back to the 2nd century BCE, I continue to be moved by both their simplicity and ongoing relevance to daily life.

Consider this sutra (1.33), from Edwin F. Bryant’s translation:

By cultivating an attitude of friendship toward those who are happy, compassion toward those in distress, joy toward those who are virtuous, and equanimity toward those who are non-virtuous, lucidity arises in the mind.

Out of all 196 sutras, Swami Satchidananda says, “whether you are interested in enlightenment or plan to ignore yoga entirely,” this is the one to remember. Why does he think it’s so important? Because – unless we live in a cave – this sutra give us something tangible and easy that we can practice every day, whoever we encounter.

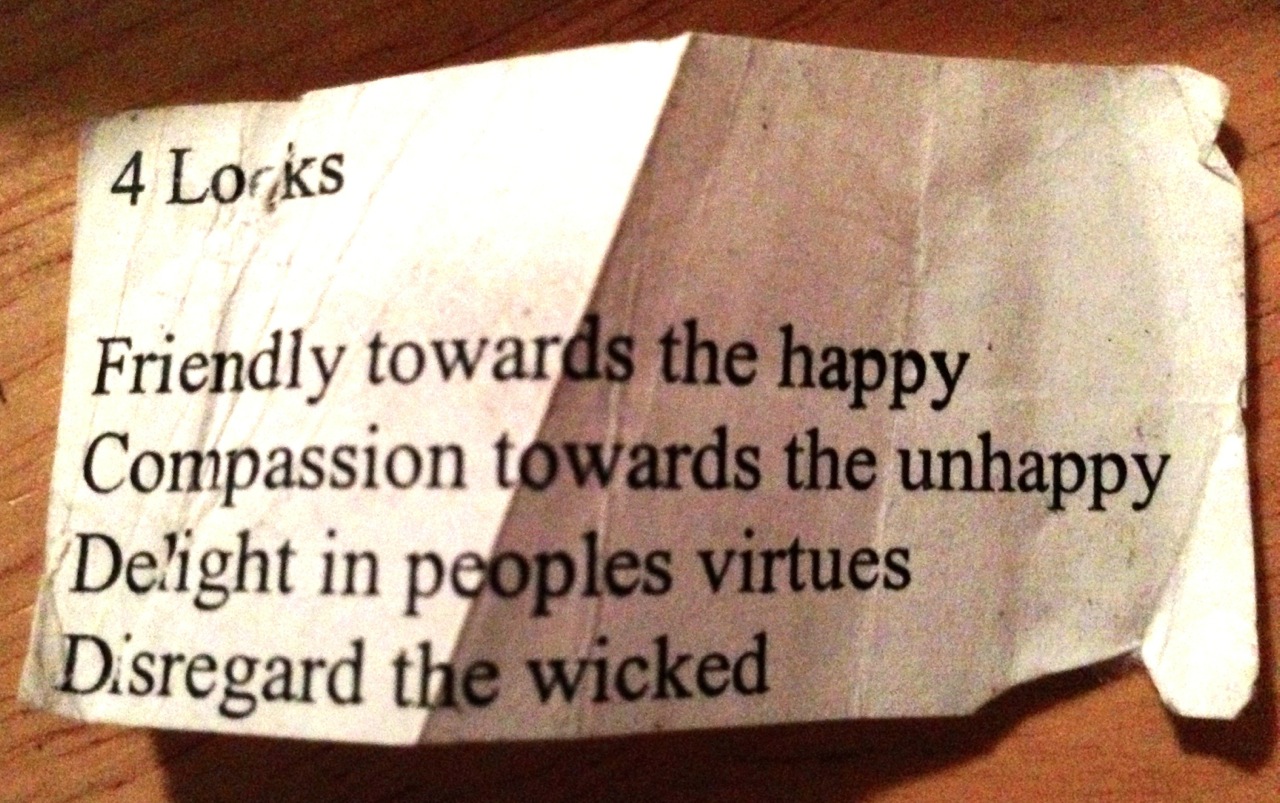

Satchidananda also offers a wonderful analogy to describe the application of this sutra: the four locks and four keys. Locks are the emotional state of any person with whom we are interacting –positive or not-so-positive. The keys are the guides to our response. Mindfully used, they help us maintain peace within – a state of being yoga teaches that we possess already – and peace without – because they offer a simple guide to help avoid conflict and suffering.

Let’s take a look at each lock and key to see how they can be put into practice.

Friendship toward those who are happy

Any number of things may be the source of someone’s happiness: a material possession, a new baby, a new job, a beautiful day… Yet we all know that when we’re in the presence of such a person, there are times when their happiness triggers feelings like envy, regret and annoyance. Why can’t it be like that for me?! Very human. And we’ve all been there.

The key? Cultivate an attitude of friendliness.

For instance, there are times I feel regretful when interacting with friends who have super-close relationships with their mothers, sharing their joys and challenges alike in this most primary relationship. I lost my mother when I was 11. Often, I feel a yearning. What might it have been like to know my mother into my adulthood? To have her enjoy my husband and stepdaughter?

I’ll never know.

But when I find wistfulness arising and choose to maintain an attitude of friendliness, I’m able to appreciate that I now, as an adult, have the opportunity to be a loving maternal figure in my family, even if it was denied me. Additionally, having been blessed with some exceptional women – Portia Nelson and Tao Porchon-Lynch – as maternal figures in my life, I can appreciate even more the fact that maternal love comes from many sources, not merely biological.

Cultivating friendliness is transformative. Rather than wallowing in a feeling of loss or lack, it gently opens the heart to be happy for others and to accept what is without resistance.

Compassion toward those in distress

To those who are in distress or otherwise unhappy, our key is to practice compassion.

I have more than 10 translations of the Yoga Sutras, and each one uses the word “compassion,” not “sympathy” or “pity.” Those other attitudes may come from a place of good intentions, but they are also responses of superiority and distance. Compassion allows us to relate with kindness and empathy.

Sympathy and pity disturb the mind by contributing to over-care – a concept I learned much about from the HeartMath Institute. If in the process of caring, your efforts produce stress or leave you feeling depleted, that’s when you’re in over-care. Instead of our care being loving, helpful and supportive, it makes us less effective, anxious, overprotective and righteous. We literally leak energy.

The solution is not to stop caring. It’s to relate with compassion. Compassion is the quality of caring that sustains.

Joy toward those who are virtuous

Witnessing the virtuous, it’s easy to notice our shortcomings. We can lapse into jealousy, self-criticism, regret. This is the ego kicking up a storm.

I once worked with a client who lamented that she was “stuck” working an office job that she hated. She made decent money, but she’d always wanted to teach. This triggered strong feelings of annoyance toward a fellow PTA member who’d recently shifted to a teaching career and loved it. In exploring my client’s feelings, we found an opportunity just waiting for her. Once she was able to move from envy to joy for this woman, she found the confidence to approach her. Not only did the woman offer to help my client navigate her own transition to teaching, they became good friends.

The key to restoring serenity is to rejoice in the virtuous. It offers an amazing opportunity to examine what it is we truly desire.

Equanimity toward those who are non-virtuous

The last part of this sutra has many variations. Where Bryant translated the word as “non-virtuous,” others have translated it as “wicked,” “impure” and “vicious.”

And in our complicated world, this lock is usually the stickiest. There are wicked people and people who are vicious. Often, our first reaction is to hurt them in some way or retaliate.

What’s important here is noting that equanimity isn’t so much about the action that we take (or don’t take) but our state of mind while observing the person. Equanimity is not about ignoring injustice. At its best, it encourages benevolent social action. Exemplars of this practice include Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr.

So if someone is causing harm, instead of getting angry and disturbing your own peace or speechifying in your mind about what a terrible person he or she is, and so on, you maintain empathetic composure. Then, if you choose to approach the individual or take any action, you will be doing so from a place of awareness. This also leaves room for the possibility that the best action to take may be no action at all – to simply walk away.

It’s important to recognize that this sutra is not only about our interactions with others. We can use it on ourselves, as well. In another noted translation of the sutras, Rev. Jaganath Carrera suggests we thus apply them:

- Befriend our own joy and celebrate personal victories.

- Practice self-compassion when unhappy.

- Feel joy in our merits and virtues.

- Practice self-forgiveness and patience for our shortcomings.

Yoga is an experience-based science. Try practicing this sutra for one week, identifying the most predominant lock (happy/distressed/virtuous/non-virtuous) you notice in every person you meet and respond with the appropriate key (friendship/joy/compassion/equanimity). Make a note of what you experience in a journal or in a personal voice memo app. Let us know how it goes!